18 January 2018 – Vancouver, CA

by Stewart Webb

The Russian Ministry of Defence announced last week that the Khmeimim air base (south-east of the Syrian city of Latakia) and the Russian naval base in the city of Tartus was under attack by a swarm of drones on the night of 5 January and into the morning of the 6th. Three drones targeted the naval base and ten swarmed the air base. The Russian Ministry of Defence states that seven of the drones were destroyed by the Pantsyr-S air defence systems and that the remaining six landed using electronic warfare hardware. Unfortunately, three exploded upon hitting the ground, which makes sense given the plywood undercarriage and fragile design.

An important development is that, like the United States and other militaries, Russia is fielding counter-Unmanned Aerial System measures and equipment. It would have had to in order to successfully bring down a number of the drones virtually intact. They purported used electronic warfare devices, but one would assume these devices had the same capabilities as the DroneGun by DroneShield that jams the controlling frequency and enables to drone to have a controlled landing as the gun targets its descent. This development demonstrates that the United States is not the only actor that is taking the emerging insurgent drone threat seriously. It also means that the Counter-Unmanned Aerial System market will be a burgeoning one as many militaries will be lining up for that technology.

The” Mysterious” Drones

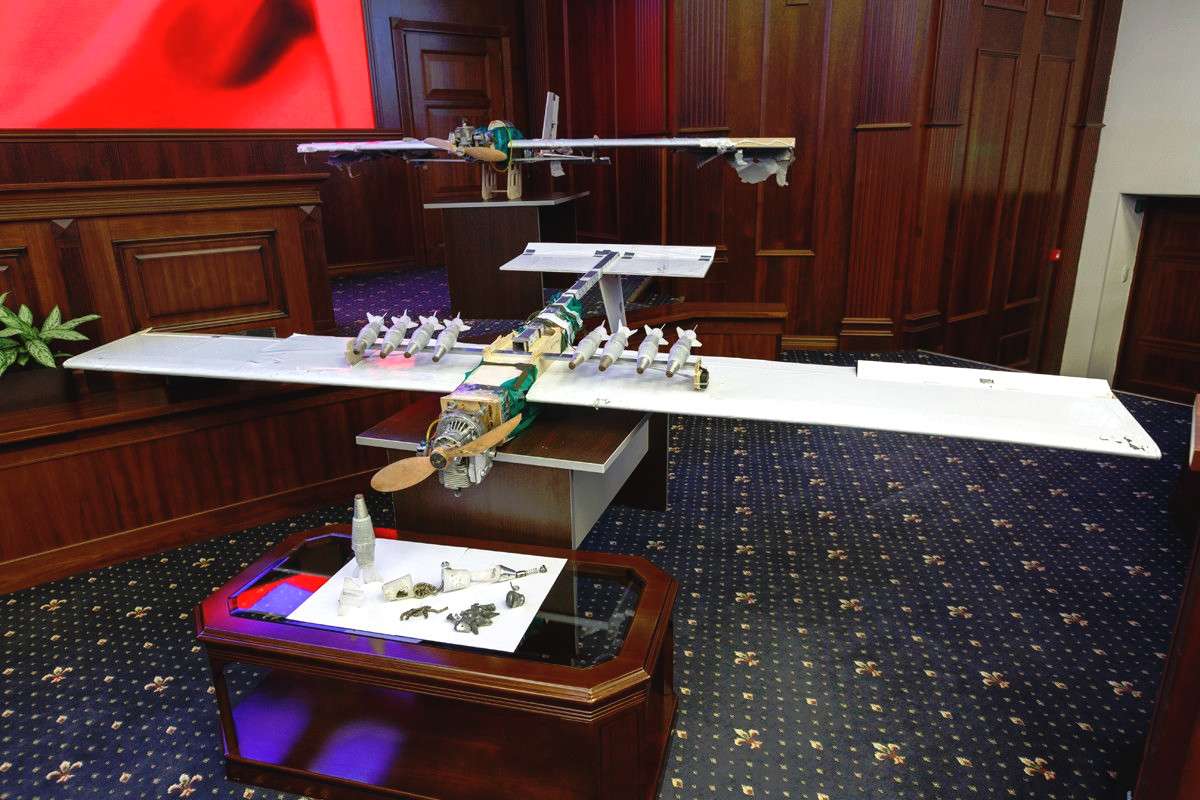

It did not take long for the Russians to put the captured drones on display. Nor was it long until the Russians accused the United States of assisting with the development of these insurgent-built drones. The Russians stated that it was a strange coincidence that a US intelligence-gathering plane flew over the area before the attack. Many of the drones utilised by ISIS or other insurgent groups have been essentially converted off-the-shelf designs. Mostly quadcopters produced by the Chinese company DJI given the share of the market that they hold. However,ISIS has been testing out various designs of fixed-wing drones, either home-built or off-the-shelf.

The drones, themselves, are unique and are not available on Amazon or on the market. The Russian Ministry of Defence claims that the drones had sophisticated GPS-technology and were able to fly over 30km due to be outfitted with a small gasoline engine. The Russians claim that these drones have an operational distance of 50 km which is an marked increase from the roughly 2 kilometers that insurgents achieve with the off-the-shelf batteries on the quadcopters. Moreover, this seems to be the first design that utilizes a gasoline-powered engine and not a battery-operated drone. These drones were comprised of plywood and Polystyrene. Polystyrene foam has been used for fixed-wing drones at ISIS drone workshops in the past. The Russians claim that the drones had a sophisticated GPS-guidance system. But even ISIS drones have utilized global positioning systems in the past. The Russians were able to ascertain the location of the launch site as the US has been able to do so in the past with other insurgent-operated drones.

Each of the mysterious drones carried 10 munitions that carried 400g of explosive with small metal balls for fragmentation and estimated effective areas of up to 50m. The munitions on the captured drones are featured on the left and to the right are drone munitions that were found at ISIS drone workshops. There are similarities. The “artisanal fuses” for example that the Russisan describe are featured here. The shell casings appeared to be made out of the same plastic material, although the design is slightly different. The reason behind this would be to save weight, and provide durability during flight at the expense of additional shrapnel in the device’s kill zone. The photo to the right is from an ISIS drone factory in Iraq from November 2016, so one would expect some advancements on the design – such as the placement of the arming pins.

Now the Russians did capture 3 drones mostly intact from their forced landing as seen below.

#Syria: new evidence showing 6 drones Rebels used to attack #Russia|n Airbase in #Khmeimim. Reportedly neutralized, 3 of them are well perserved. pic.twitter.com/LsF5cx7ByE

— Qalaat Al Mudiq (@QalaatAlMudiq) January 10, 2018

But these drones are not unique in the theater as there have been sightings of very similar drones. An investigation done by the Daily Beast back in October revealed that a remarkably similar drone was available on the Black Market in Syria. The photo below was photographed days before the attack on 1 January by Syrian Ahrar al-Sham group. This group has shifted its allegiances throughout the war between the rebels and Islamists. It seems that this group may have been the perpetrators of this attack. There have been no known links between this group and ISIS, but there has been a technological transfer between all groups as one group learns from one another because of seized territory or equipment. However, as the Daily Beast revealed in October, the perpetrators may have just purchased 13 drones from the Black Market, which unto itself is a worrying concept if they are that readily available.

إسقاط طائرة استطلاع للنظام حركة أحرار الشام الاسلامية pic.twitter.com/8dbwnlIdQl

— محمد الفريد (@fredabo222) January 1, 2018

Update

It seems the militants attacked #Khmeimim air base by drones carrying bombs.

Injuries reported from the Russian side.— Kevork Almassian (@KevorkAlmassian) January 6, 2018

These drones may very well be that readily available. The Bellingcat pointed out that a Russian news agency reported that another remarkably similar drone, with a gasoline-powered engine, was shot down near Homs before the attack on the Russian bases. This drone was also outfitted with what looked like a GPS-antennae. With the drone purportedly on the market and a similar drone being utilized elsewhere in the country – it seems that it may not be group ingenuity, but just market availability. Given that there are some similarities between ISIS drones and these drones with similar materials in the construction of the fuselage and the munitions – it could be feasible that a former ISIS drone maker is selling his own wares. Regardless, these drones were not off-the-shelf and it appears that the Polystyrene and even the gasoline engine were readily available. This means that the design and building of these drones should be seen as cheap. Comparatively, an off-the-shelf DJI drone can cost hundreds of dollars, excluding redesigning for IED-release or -detonation and this design does not seem to cost that much. Moreover, DJI has been working on locking its drones so they would not operate in certain regions or localized areas, such as downtown Washington, DC.

This being said, the advancements of a gasoline-powered engine should not be overlooked. Many groups learn from one another and build on concepts. One of the best examples would be the rebels and terrorists alike in Syria have been developing teleoperated sniper or machine gun emplacements. Ingenuity has been one of the driving forces during this ongoing conflict and with every insurgency. The evolution of insurgent drones needs to be taken seriously by security forces around the world as insurgent or terrorist groups will be taken note of those advancements. The Turkish military brought down a PKK quadcopter in November. The Mexican Cartels are now using explosive-laden drones. Even the Houthi rebels in Yemen are operating explosive-laden drone boats against Saudi naval forces. Pandora’s box has been opened when it comes to terrorist or insurgent use of drones. Now the last thing that came out of Pandora’s box was hope, but that may not be the case with the evolving threat. Russia may have cried wolf in this case as it is a drone that has made its debut back in October, but the way it was used is another matter. No other attack has had a swarm of drones operating at once, but if home constructed drones are now markedly cheaper than off-the-shelf – expect more swarm attacks in the future.

Feature Photo: Captured insurgent drone on display by Russia – Russian Ministry of Defence, 2018

Inset Photo:Munitions from one of the drones – Russian Ministry of Defence, 2018

Inset Photo: Photo from the Conflict Armament Research report: “ISIS’ Multi-Role IEDs”, published April 2017 – Conflict Armament Research, 2018

DefenceReport’s Analysis is a multi-format blog that is based on opinions, insights and dedicated research from DefRep editorial staff and writers. The analysis expressed here are the author’s own and are separate from DefRep reports, which are based on independent and objective reporting.